A definite positive point in this experiment is the fact that not a single animal was harmed in the course of the experiment.

- What is the point of the Schrodinger's cat experiment? Isn't it absurd?

- Description of the experiment

- Explanation in simple words

- Explanation of the Schrödinger experiment

- What Schrödinger wanted to show

- Schrodinger's cat: is he alive or not? The essence of the experiment

- The observer effect in data handling

- The observer effect in linguistics

- masterok

- Schrödinger's cat. What it is in simple terms

- The essence of Schrodinger's Cat experiment

- masterok

- Who is Schrödinger's cat and how does it affect everyone's life?

- How do you use this in real life?

What is the point of the Schrodinger's cat experiment? Isn't it absurd?

The point is precisely the absurdity. Schrödinger was dealing with physical objects of the microcosm, for which exactly what is described in the experiment is true: the particle is both "alive" and "dead. This mental experiment is intended to show that this interpretation itself causes problems if one tries to model the macrocosm as well. If a particle is "both alive and dead at the same time," then there is a way to make the state of the macroobject (the cat) dependent on the state of the particle. But for macroobjects such "simultaneity" is physically absurd, it makes absolutely no sense to torture the animal. It is clear in advance what will happen to the cat: alive until the detector is triggered (until the particle goes from "both alive and dead" to "dead"), and after that dead. The thought experiment raises the question of how to describe this according to the rules of quantum mechanics.

Such ways are related to different "interpretations" of quantum mechanics. For example, in Copenhagen interpretation a cat is not alive and dead at the same time, and in multiverse interpretation a living cat and a dead cat belong to different "worlds". The final decision on how to correctly interpret what happens to macroobjects has not yet been reached, but Schrödinger's contribution (among other things) is that he formulated the problem in such a clear pictorial way.

Description of the experiment

Erwin Schrödinger's original paper was published in 1935. In it the experiment was described using the technique of comparison or even impersonation:

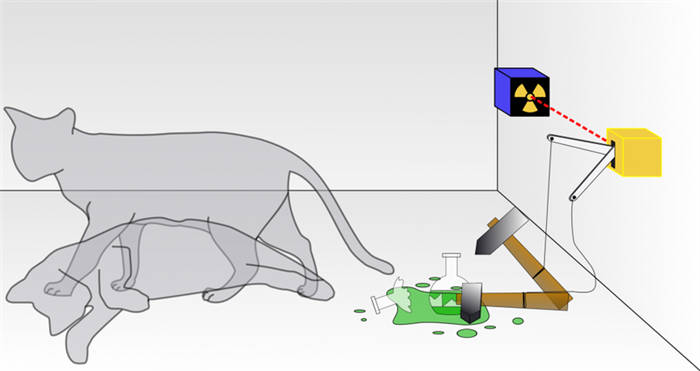

It is also possible to construct cases in which the burlesque is sufficient. Let some cat be locked in a steel chamber together with the following devilish machine (which must be independent of the cat's intervention): inside the Geiger counter there is a tiny amount of radioactive substance, so small that only one atom can decay in an hour, but with the same probability may not decay; if this happens, the reading tube discharges and a relay is triggered, which breaks the flask with hydrocyanic acid.

If we leave this whole system to itself for an hour, we can say that the cat will be alive after that time, as long as the decay of the atom does not occur. The first decay of the atom would poison the cat. The psi-function of the system as a whole would express this by mixing in or smearing the living and dead cat (pardon the expression) in equal parts. It is typical in such cases that the uncertainty originally confined to the atomic world is transformed into a macroscopic uncertainty that can be eliminated by direct observation. This prevents us from naively accepting the "blur model" as reflecting reality. This in itself does not mean anything fuzzy or contradictory. There is a difference between a fuzzy or unfocused photo and a picture of clouds or fog.

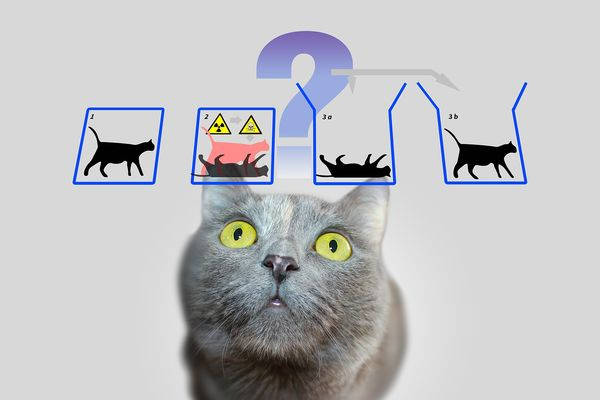

- There is a box and a cat. In the box there is a mechanism containing a radioactive atomic nucleus and a tank of poison gas. The parameters of the experiment are chosen so that the probability of the nucleus decaying in 1 hour is 50%. If the nucleus decays, the container with the gas opens and the cat dies. If the nucleus does not disintegrate, the cat is alive and well.

- We close the cat in a box, wait an hour, and ask ourselves: is the cat alive or dead?

- Quantum mechanics tells us that atomic nucleus (and hence cat) is in all possible states simultaneously (see quantum superposition). Before we open the box, the system "cat-nucleus" is in the state "nucleus decayed, cat dead" with 50% probability and in the state "nucleus not decayed, cat alive" with 50% probability. It turns out that the cat sitting in the box is both alive and dead at the same time.

- According to the modern Copenhagen interpretation, the cat is alive/dead without any intermediate states. And the choice of the nucleus decay state does not take place at the moment of opening the box, but when the nucleus enters the detector. Because the reduction of the wave function of the cat-detector-nucleus system is not related to the human observer of the box, but to the detector-observer of the nucleus.

Explanation in simple words

According to quantum mechanics, if nucleus of an atom is not observed, then its state is described by mixture of two states – decayed nucleus and undecayed nucleus, hence, the cat, sitting in the box and representing the nucleus of atom, is both alive and dead. If you open the box, the experimenter can see only one particular state – "the nucleus has decayed, the cat is dead" or "the nucleus has not decayed, the cat is alive".

The bottom line in human terms: Schrödinger's experiment showed that, in terms of quantum mechanics, the cat is both alive and dead, which cannot be. Consequently, quantum mechanics has significant flaws.

The question is as follows: when the system ceases to exist as a mixture of two states and chooses one particular state? The purpose of the experiment is to show that quantum mechanics is incomplete without some rules, which indicate under what conditions the collapse of the wave function occurs, and the cat either becomes dead or remains alive, but ceases to be a mixture of both. Since it is clear that the cat must necessarily be either alive or dead (there is no state between life and death), this would be analogous for the atomic nucleus. It must necessarily be either decayed or undecayed (Wikipedia).

Explanation of the Schrödinger experiment

An unstable atomic nucleus can be seen as an object of the quantum world, because it can stay in one of two certain states: decayed or not decayed. At the same time before the fact of observation it stays simultaneously in both states (such mixed state is called "superposition").

The meaning of Schrödinger's experiment can be explained in simple words as follows:

- The state of the cat is directly related to the state of the atomic nucleus (life ceases at the moment of decay);

- If we say that the nucleus exists simultaneously in two opposite states, the same can be said about the cat (both alive and dead at the same time);

- One can only unambiguously judge the state of the cat (and the atom) once the box has been opened (that is, when the interaction of the observer with the system, which was previously isolated, has taken place);

- From the point of view of common sense it is impossible to say that Schrödinger's cat is both alive and dead at the same time, and its state is determined at the moment when the researcher opens the container;

- But quantum mechanics says exactly that.

So the purpose of Schrödinger's experiment was to demonstrate the contradiction of one of the key principles of quantum mechanics to logic and common sense. The author insisted that the generally accepted Copenhagen interpretation of CM is incomplete because it does not describe the clear criteria at which the so-called collapse of the wave function occurs (the very moment when the superposition is replaced by one of the possible states).

What Schrödinger wanted to show

Erwin Schrödinger devoted a large part of his life to theoretical research in quantum mechanics, so he was certainly not its opponent or critic. The scientist was not satisfied with the Copenhagen interpretation, which his colleagues accepted as the most valid. Bringing one of the key theses of quantum mechanics to the point of absurdity, he did not try to disprove it, but only he only called attention to the incompleteness of the accepted interpretation.

He believed that for completeness it is necessary to precisely define the conditions under which collapse of the wave function (i.e., the system goes from superposition to one particular quantum state). From the formulations adopted at that time, one could conclude that a person is capable of influencing the state of matter literally with one look. And allegedly it is at the moment of observation that the system moves from superposition to one particular state.

In simple words, if we consider Schrödinger's experiment within the Copenhagen interpretation, then the cat becomes alive or dead only when the scientist opens the box, and not at the moment when the "infernal machine" is triggered. The scientist did not dispute the existence of superposition and the uncertainty principle in the quantum world. He challenged the so-called "observer paradox," according to which it's the observer at the moment of observation that takes the system out of superposition.

Schrodinger's cat: is he alive or not? The essence of the experiment

We've all heard of the famous Schrodinger's cat, but do we know what kind of cat he really is? Let's break it down and try to talk about Schrödinger's famous cat in simple words.

Schrodinger's cat is an experiment conducted by Erwin Schrodinger, one of the founding fathers of quantum mechanics. It's not an ordinary physical experiment, but a it's a mental.

We must admit that Erwin Schrodinger was a man with a very rich imagination.

So what do we have as an imaginary basis for the experiment? There is a cat in a box. In the box there is also a Geiger counter with some very small amount of radioactive substance. The amount of substance is such that the probability of one atom decaying and not decaying in one hour is the same. If the atom decays, a special mechanism will be triggered to break the flask of hydrocyanic acid, and the poor cat will die. If the atom does not decompose, the cat will continue to sit quietly in the box and dream of sausages.

What is the essence of Schrodinger's cat? Why was it necessary to come up with such a surreal experience in the first place?

According to the results of the experiment, we only know whether the cat is alive or not when we open the box. From the point of view of quantum mechanics, the cat is in two states at the same time (just like an atom of matter) – both alive and dead at the same time. This is the famous Schrodinger's cat paradox.

Naturally, this cannot be. Erwin Schrodinger set up this mental experiment to show imperfection of quantum mechanics in transition from subatomic systems to macroscopic ones.

The observer effect in data handling

When different researchers select and process data, they each use their own methods. But even relatively innocuous differences at the selection stage can lead to different analyses of the same data. This effect is created by the researchers themselves, either directly or indirectly. For example, in a data bank, information for one period was mistakenly included in another and published in the public domain, and the researcher did not pay attention to it or did not double-check information with other sources. Similarly, different programs that use the same method of analysis may produce small but significant biases.

When collecting and analyzing data, researchers suggest taking this effect into account: even small deviations in the results can have significant consequences.

The observer effect in linguistics

In sociolinguistics, the term "observer's paradox" was introduced by linguist William Labov. He noted that native speakers, when speaking to linguistic scientists and knowing that their speech will be used in research, unconsciously distort it: they begin to speak formally and unnaturally. But it is natural, undistorted speech that the researcher needs. Thus, **the observer influences the data obtained: if he were not present, the speaker would use ordinary vernacular language.

To minimize distortions and circumvent the "observer paradox," scholars use special techniques: for example, they observe covertly or tell native speakers false research targets.

masterok

Many people have heard this expression, but probably not everyone understands even its simplified meaning. Let's try to understand it without complicated theories and formulas.

«Schrodinger's catThe famous mental experiment of the famous Austrian theoretical physicist Erwin Schrödinger, who is also a Nobel Prize winner, is called "Schrödinger's cat. With this fictional experience, the scientist wanted to show the incompleteness of quantum mechanics in the transition from subatomic systems to macroscopic systems.

Erwin Schrodinger's original paper was published in 1935. Here is the quote:

One can also construct cases in which the burlesque is sufficient. Let some cat be locked in a steel chamber together with the following devilish machine (which must be independent of the cat's intervention): there is a tiny amount of radioactive substance inside the Geiger counter, so small that only one atom can decay in one hour, but with equal probability it may not; if this happens, the reading tube discharges and a relay is triggered which releases a hammer which breaks a flask of hydrocyanic acid.

If we leave this whole system to itself for an hour, we can say that the cat will be alive after that time, as long as the decay of the atom does not occur. The first decay of the atom would poison the cat. The psi-function of the system as a whole would express this by mixing in or smearing the living and dead cat (pardon the expression) in equal parts. It is typical in such cases that the uncertainty originally confined to the atomic world is transformed into a macroscopic uncertainty that can be eliminated by direct observation. This prevents us from naively accepting the "blur model" as reflecting reality. This in itself does not mean anything fuzzy or contradictory. There is a difference between a fuzzy or unfocused photo and a picture of clouds or fog.

- There is a box and a cat. In the box there is a mechanism containing a radioactive atomic nucleus and a tank of poison gas. The parameters of the experiment are chosen so that the probability of the nucleus decaying in 1 hour is 50%. If the nucleus decays, the container with the gas opens and the cat dies. If the nucleus does not disintegrate, the cat is alive and well.

- We close the cat in a box, wait an hour, and ask ourselves: is the cat alive or dead?

- Quantum mechanics tells us that atomic nucleus (and hence cat) is in all possible states simultaneously (see quantum superposition). Before we open the box, the system "cat-nucleus" is in the state "nucleus decayed, cat dead" with 50% probability and in the state "nucleus not decayed, cat alive" with 50% probability. It turns out that the cat sitting in the box is both alive and dead at the same time.

- According to the modern Copenhagen interpretation, the cat is alive/dead without any intermediate states. And the choice of the nucleus decay state does not take place at the moment of opening the box, but when the nucleus enters the detector. Because the reduction of the wave function of the "cat-detector-nucleus" system is not related to the human observer of the box, but to the detector-observer of the nucleus.

Schrödinger's cat. What it is in simple terms

Schrödinger's Cat. – is a thought experiment proposed by the Austrian physicist theorist Erwin Schrödinger. This talented scientist received the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1933.

Through his famous experiment he wanted to show the incompleteness of quantum mechanics in the transition from subatomic systems to macroscopic ones.

Erwin Schrodinger tried to explain his theory using the original example of a cat. He wanted to make it as simple as possible, so that his idea would be understandable to anyone.

The essence of Schrodinger's Cat experiment

The physicist published his theory in 1935. Here is an excerpt from Schrödinger's original article, where he described the experiment. Don't be frightened if you don't understand it right away – below we will try to explain everything in simple words.

Suppose a certain cat is locked in a steel chamber together with such an infernal machine (which must be protected against direct intervention by the cat): inside the Geiger counter there is such a tiny amount of radioactive substance that only one atom can decay in one hour, but it is just as likely not to decay; if this happens, the reading tube discharges and a relay is triggered, which breaks the flask of hydrocyanic acid.

If we leave this whole system to itself for an hour, we can say that the cat will be alive after that time, as long as the decay of the atom does not occur.

The first decay of the atom would poison the cat. The psi-function of the system as a whole would express this by mixing in or smearing the living and dead cat (pardon the expression) in equal parts.

It is typical in such cases that the uncertainty originally confined to the atomic world is transformed into a macroscopic uncertainty that can be eliminated by direct observation.

This prevents us from naively accepting the "blur model" as reflecting reality. This in itself does not mean anything fuzzy or contradictory.

There is a difference between a fuzzy or unfocused photo and a picture of clouds or fog.

In other words, we have a box and a cat. The box contains a device with a radioactive atomic nucleus and a container of poison gas.

In the experiment, the probability of the nucleus decaying or not decaying is equal to 50%. Consequently, if it decays, the animal will die, and if the nucleus does not decay, Schrodinger's cat will live.

masterok

Many people have heard this expression, but perhaps not everyone understands even its simplified meaning. Let's try to understand it without complicated theories and formulas.

«Schrodinger's cat" is the name of the famous mental experiment of the famous Austrian theoretical physicist Erwin Schrödinger, who is also a Nobel Prize winner. With this fictional experience, the scientist wanted to show the incompleteness of quantum mechanics in the transition from subatomic systems to macroscopic systems.

Erwin Schrodinger's original paper was published in 1935. Here is the quote:

One can also construct cases in which the burlesque is sufficient. Let some cat be locked in a steel chamber together with the following devilish machine (which must be independent of the cat's intervention): inside the Geiger counter there is a tiny amount of radioactive substance, so small that only one atom may decay in one hour, but with the same probability may not decay; if this happens, the reading tube discharges and a relay is triggered, which releases a hammer that breaks the flask with hydrocyanic acid.

If we leave the whole system to itself for an hour, we can say that the cat will be alive after that time, as long as the decay of the atom does not occur. The first decay of the atom would poison the cat. The psi-function of the system as a whole would express this by mixing in or smearing the living and dead cat (pardon the expression) in equal parts. Typical of such cases is that the uncertainty originally confined to the atomic world is transformed into a macroscopic uncertainty that can be eliminated by direct observation. This prevents us from naively accepting the "blur model" as reflecting reality. This in itself does not mean anything fuzzy or contradictory. There is a difference between a fuzzy or unfocused photo and a picture of clouds or fog.

- There is a box and a cat. In the box there is a mechanism containing a radioactive atomic nucleus and a tank of poison gas. The parameters of the experiment are chosen so that the probability of nucleus decay in 1 hour is 50%. If the nucleus disintegrates, the container with the gas opens and the cat dies. If the nucleus does not disintegrate, the cat stays alive and well.

- We close the cat in a box, wait an hour and wonder if the cat is alive or dead.

- Quantum mechanics tells us that atomic nucleus (and hence cat) is in all possible states simultaneously (see quantum superposition). Before we open the box, the cat-nucleus system is in the state "nucleus decayed, cat dead" with 50% probability and in the state "nucleus not decayed, cat alive" with 50% probability. It turns out that the cat sitting in the box is both alive and dead at the same time.

- According to the modern Copenhagen interpretation, the cat is alive/dead without any intermediate states. And the choice of the nucleus decay state does not occur at the moment of opening the box, but when the nucleus enters the detector. Because the reduction of the wave function of the "cat-detector-nucleus" system is not related to the human observer of the box, but to the detector-observer of the nucleus.

Who is Schrödinger's cat and how does it affect everyone's life?

Probably almost everyone who is reading this post at least once heard about the famous mental experiment from the field of quantum mechanics called "Schrodinger's cat", about the cat that is "both alive and dead at the same time". But have you ever wondered how this thought can be used in practice in real life?

Back in 1935, the Austrian theoretical physicist Erwin Schrödinger published an article with a mental experiment in which he wanted to show the incompleteness of quantum mechanics in the transition from subatomic systems (microbodies) to macroscopic ones (objects of the surrounding world).

It is also possible to construct cases in which the burlesque is sufficient. A certain cat is locked in a steel chamber along with the following infernal machine (which must be protected from direct intervention by the cat): inside the Geiger counter is a tiny amount of radioactive substance, so small that within an hour . only one atom can decay, but with equal probability it may not; if it does, the reading tube discharges and a relay is triggered, which breaks a flask of hydrocyanic acid. If we leave this whole system to itself for an hour, we can say that the cat will be alive at the end of that time, as long as the atom the decay of the atom doesn't happen. The first decay of the atom would poison the cat. The psi-function of the system as a whole would express this by mixing in or smearing the living and dead cat (pardon the expression) in equal parts.

Typical in such cases is that the uncertainty originally confined to the atomic world is transformed into a macroscopic uncertainty that can be eliminated by direct observation. This prevents us from naively accepting the "blur model" as reflecting reality. This in itself does not mean anything fuzzy or contradictory. There is a difference between a fuzzy or unfocused photo and a shot of clouds or fog.

How do you use this in real life?

Unfortunately or fortunately, the human brain is arranged in such a way that it subjects absolutely any action, phenomenon or external factor to a thorough analysis, the results of which affect our opinion about the object of analysis. Therefore, people tend to doubt anything, especially when they are faced with uncertainty. Does the girl/boyfriend like me? Will I get a promotion? Will I be able to achieve my goal? The list of doubts can range from the size of a notebook page to entire almanacs.

In fact, everything is simpler than we imagine in our heads. Recall Schrodinger's cat experiment – the cat is either dead or alive. There is no third option, but we won't know the outcome of the experiment until we open the box. Let's project this onto our life problems: project your problem in your head and choose the two most probable outcomes of an event, preferably the most positive and the most negative result of the consequences of your actions. All you have to do is open the box, that is, do what you doubt, or wait for event X to happen.

This comparison is quite aptly used by the hero of the TV series "The Big Bang Theory: